Engineering Insights

In the 1980s electronically controlled ignition and fuel injection systems were the first major embedded systems deployed for the automotive industry, as ignition and injection analog units started to be progressively replaced by the more controllable digital alternatives facilitated by the availability of microcontrollers.

Electronically-controlled ignition and fuel-injection systems were the first major embedded systems deployed in the automotive industry, and originally the acronym ‘ECU’ stood for ‘Engine Control Unit‘. Though that definition is still technically valid, it has since been redefined, because of its cross-sector popularity, into the more general ‘Electronic Control Unit‘.

A modern car is likely to have forty or fifty ECUs, with high-end models reaching a hundred or more. These modules are spread over functions from engine management and transmission control to passive safety systems, driver assistance, anti-lock braking, habitat control, infotainment, and navigation, amongst other functions. Indeed, it’s estimated that electronics will reach 35% of the average cost of a car by 2020.

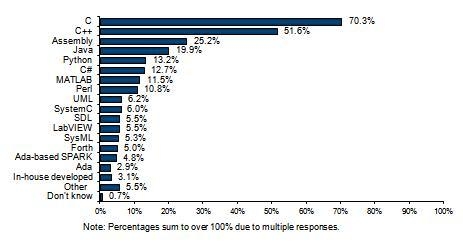

Since the software underpinning these systems tends to be proprietary, it’s difficult to get hard statistics about the programming languages used to create them. My own industry experience as an engineer in the automotive sector indicates that C predominates, followed by C++. A 2011 VDC Research survey, covering the entire embedded industry, seems to support this:

Narrowing down the analysis to safety-critical systems, we can quickly discount languages such as C#, Java, Python, or Perl. These might be good for infotainment or navigation systems but will fall short of functional safety usability due to the difficulty of qualifying their related virtual machines (VMs), compilers, and interpreters. Modeling languages such as UML, SysML, SDL, and MATLAB still pass through C/C++ generated code on their way to generating executable binaries. Besides C and the increasingly popular C++, the traditional alternatives remain assembly language and Ada, both already in wide usage in the military and aerospace sectors.

This first article in a series of three discusses the evolution of C-based programming techniques in the automotive industry, under pressure from applications that proved increasingly demanding in terms of both functional safety and behavioral complexity.

Before examining the peculiarities of C, let’s talk about its roots — about how the language was conceived, its subsequent adoption in the embedded sector, and its relationship with functional safety.

The rise of C in the 1970s

C originated from the early development of the Unix operating system: it was conceived by Dennis Ritchie between 1969 and 1973 at Bell Labs as a better alternative to assembly language for porting Unix implementations on Programmed Data Processor (PDP) machines.

Ritchie’s new language was able to utilize constructs that could be efficiently mapped to machine instructions, offering a more intuitive programming environment than assembly, with a minimal performance penalty. Able to reconcile high-level structured programming language concepts with low-level mechanisms for direct memory access, C quickly became one of the most used programming languages on a wide range of operating systems and hardware platforms.

It also became the de facto option in embedded software development, for a number of reasons.

Firstly, as mentioned, it provides very efficient binary code generation (no more than double the footprint of equivalent code written directly in assembly) — a significant improvement over other programming languages.

Secondly, it is supported by a wide range of cross-platform compilers covering the most important classes of CPU, as well as more marginal ones. Migration is generally made easier, usually with less need for platform-specific changes, and less need for additional runtime support libraries.

Additionally, C combines efficient mechanisms for direct memory access and supports easy integration and exchange of data with assembly routines addressing hardware-specific needs.

C and Functional Safety

Much of the discussion about functional safety in the automotive sector centers around the ISO 26262 standard first released in 2011. Though ISO 26262 formally defines a framework for functional safety in automotive engineering, it is actually just an adaptation of a generic functional safety standard applicable to any industry: IEC 61508 – Functional Safety of Electrical/Electronic/Programmable Electronic Safety-related Systems, first released in 1998 (parts 1-4) with supporting examples published in 2000 (parts 5-7).

Certainly, C is not the best option for supporting the high standard of robustness needed for critical safety applications. Many of the flexibility features related to both execution flow and data handling — features that originally made C the first choice for embedded system software — are now considered a source of risk from the functional safety perspective.

The criticism falls into two categories: the non-deterministic behavior of C for some features, and its propensity to permit software development bugs (we’ll take a look at both these aspects in the next post).

But in spite of these caveats, C is still one of the most mature and widely supported programming languages, with an impressive diversity of high-performing and stable compilers for many CPU architectures — some of them specifically addressing the functional safety requirements of ISO 26262 or IEC 61508.

C also has extensive support in terms of tools such as static and dynamic code analyzers, debuggers, testing frameworks, and metrics gathering, among others, inspiring a high level of trust in the development community for the use of C even in safety-critical applications.

C’s popularity in functional safety-related systems is also based on simple economics; each company tends to have existing C-based legacy code to reuse, which can cut the cost of adapting to new standards.

MISRA C: The safe subset of C

In support of entrenching C as the industry standard for safety-critical embedded software, the first version of MISRA C was released by the Motor Industry Software Reliability Association in 1998. Unlike IEC 61508 and the later ISO 26262, which sought to cover the full system, hardware plus software, and the entire development process, MISRA C focused on writing robust code in C.

Though this new standard initially targeted the automotive industry, MISRA C was widely adopted by other industries including aerospace, railways, defense, and medical devices, and went on to define the state of the art in terms of reliability and robustness in a C based coding environment.

In the next post, we’ll take a look at the potential safety-related pitfalls associated with using a language as mature and flexible as C, and also at some best practice guidelines for developers looking to write robust but secure code.

References:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C_(programming_language)

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/277931/automotive-electronics-cost-as-a-share-of-total-car-cost-worldwide/

- http://blog.vdcresearch.com/embedded_sw/2011/06/2011-embedded-engineer-survey-results-programming-languages-used-to-develop-software.html

- ISO26262- Part 6

- MISRA C:2012